America’s greatest strength, and its greatest weakness, is our belief in second chances, our belief that we can always start over, that things can be made better.

—Anthony Walton

Within the last 500 years, millions of immigrants have been drawn to America’s coasts in search of a second chance. Leaving homes and families, they have journeyed from their native lands in hopes of achieving the fabled American dream—the idea that anyone, with enough hard work and discipline, can rise from humble beginnings and achieve happiness, success, wealth, or status. For many immigrants, even the chance for a better life has made America a worthwhile place to settle. To the immigrant, America has often been characterized by the freedom to try and fail, but then to try again and again until success is finally reached.

America’s immigration story has largely been one of hope, but it has not always been perfect. As you will see in this lesson, some immigrants were carried to America against their will, some faced discrimination upon their arrival, and some were barred from entering America because of their race. Every generation makes its mistakes, but it is up to those that follow to learn from them. Fortunately, many of the prejudices of prior years have been overcome by the valiant efforts of visionary people. But we can still do much more to ensure that the American dream becomes a reality for all people. As you read about the history of American immigration, think of how it has affected your life and the culture in which you have grown up. The American ideal of a second chance holds true for us today. We now have a chance to apply the strengths of past generations, to overcome their weaknesses, and to ensure an America characterized by greater acceptance and equality for all.

Many scientists believe the first people to settle the American continent were the Native Americans who traveled over the Bering Strait 20,000 years ago. Long after their settlement, around A.D. 1000, Vikings discovered America, followed five hundred years later by the Europeans.1

The European migration began with the Spanish, who started settling the New World in the sixteenth century. British, Dutch, and Swedish settlers soon followed, establishing by the early seventeenth century several small colonies in what is now New England, Virginia, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware.

At the time, traveling across the Atlantic Ocean was not easy or comfortable. Everyone had to endure a two-to-three-month boat ride, along with all its discomforts, such as seasickness, overcrowding, limited food rations, and disease.2 Sometimes travelers did not survive the experience. But to the individuals who chose to make the journey, the chances for land, wealth, political refuge, and religious freedom made all the risks and sacrifices of the journey worthwhile.

Unfortunately, many early American immigrants were slaves. Beginning as early as 1619, native residents of Africa and the Caribbean were captured by slave traders, transported like cargo to the New World, and then sold against their will into servitude. The first U.S. census, taken in 1790, revealed that people of African descent made up 19.27 percent of the 3.9 million people living in America. Most were slaves.3

The slave trade often separated spouses, parents, children, brothers, and sisters. Olaudah Equiano experienced the cruelty and separation of slavery and described it in his 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa the African. Equiano was just eleven years old when he and his sister were kidnapped from their African village by slave traders. Confused and grief-stricken, Equiano and his sister were separated, and Equiano was held in captivity for seven months. Eventually, British slave traders purchased him and transported him by boat to Barbados and then to Virginia, where they sold him as a slave to a British naval officer.

In the following passage, Equiano describes the deplorable conditions he experienced on the slave boat as he crossed the Atlantic Ocean. For the slaves, immigration meant hardship without the hope of a better life. Many years would pass before slavery in America would come to an end.

When I looked round the ship too and saw a large furnace of copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, everyone of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow. . . .

I now saw myself deprived of all chance of returning to my native country, or even the least glimpse of hope of gaining the shore which I now considered as friendly. . . . I was not long suffered to indulge my grief; I was soon put down hinder the decks, and there I received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life: so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me. . . .

The closeness of the place and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious5 perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice,6 as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women and the groans of the dying rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable . . . and I began to hope that death would soon put an end to my miseries.

Another kind of unpaid labor, called indentured servitude, existed in early colonial America. Many European immigrants traveled willingly to America but did not have enough money to finance the journey or buy land. They agreed instead to work for several years as indentured servants in exchange for the promise of land at the end of their servitude.7

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, several European nations established colonies in North America. However by the mid-eighteenth century, the British colonies had become the most prosperous. Many skilled British workers had migrated to America and were continuing to do so at a rate that alarmed the British Parliament.8

The relationship between Britain and the colonies soured quickly as King George III and Parliament imposed restrictive legislative acts and new taxes on the colonies. The taxes and restrictions were intended to protect the British economy, pay for British troops in America, and finance the French and Indian War. Instead, the acts angered the colonists, who felt their civil rights had been violated because they had not been given any representation in Parliament. The Parliamentary acts benefitted England, but at significant expense to the colonies. Parliament’s refusal to grant representation to the colonists simply reinforced in their minds the idea that Parliament and the king had become power hungry and tyrannical.

Protesting and petitioning on the part of the colonists did not resolve the conflict, and soon violence erupted. The colonies declared independence in 1776, and the American Revolution followed. In 1783, America claimed an unlikely victory over Great Britain, and the United States of America emerged as a legitimate new nation.

Immigrants didn’t immediately begin pouring into the United States following its revolutionary victory. Several factors of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries prevented most would-be immigrants from leaving their homelands in Europe for America. Conflict between England and France tied up most transatlantic travel, followed by the War of 1812 between England and the United States, which prevented immigration even more. In addition, many European nations of the time restricted movement beyond their borders to retain young men of military age.9

Immigrants started to arrive in steadily increasing numbers in 1814, after a peace treaty brought an end to the War of 1812. It continued to climb at a steady rate until the 1840s, when a potato famine in Ireland and revolutionary commotion in Germany sent millions of people fleeing to America for refuge. This marked the first of many mass immigrations into the United States.

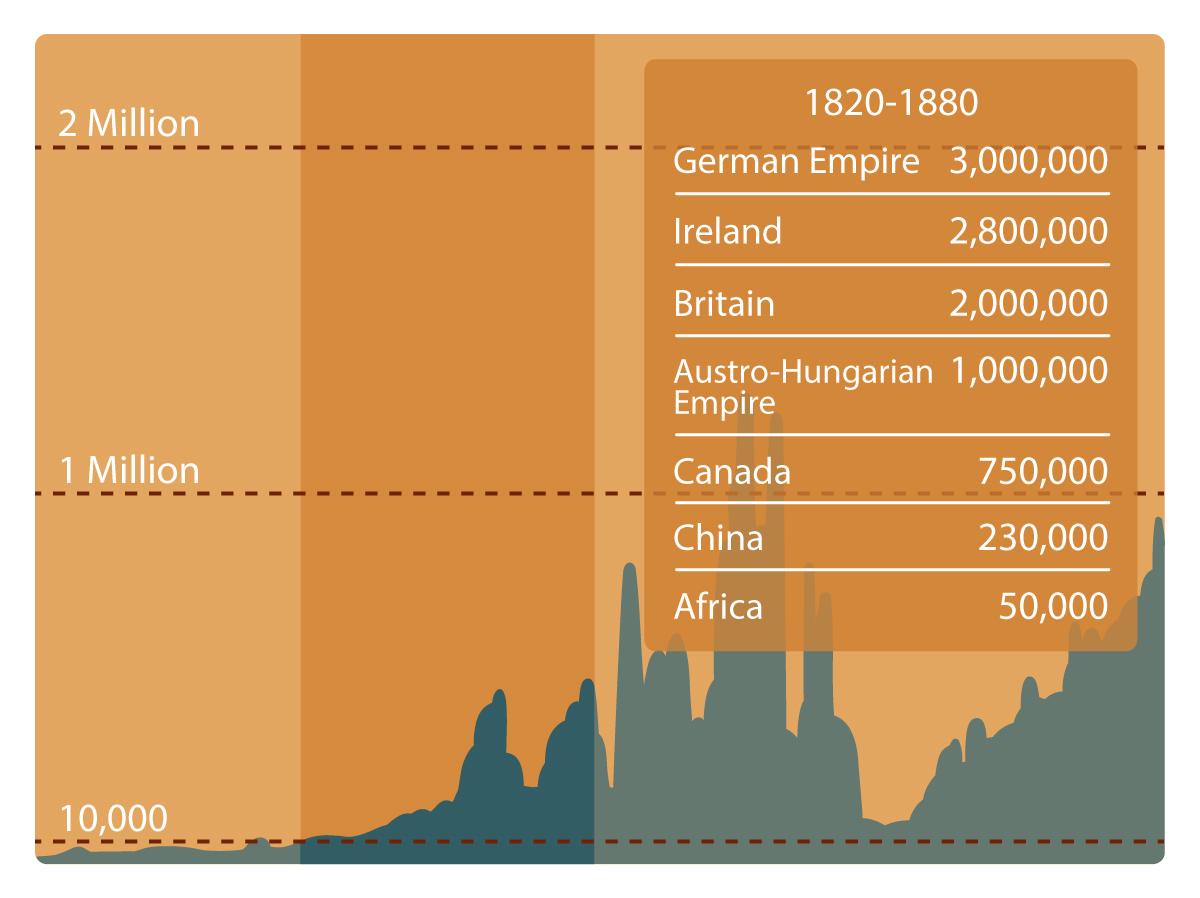

The figure above shows the impact these and other events had on U.S. immigration trends. Although the Irish and German immigrations of the mid-nineteenth century were quite large for the time, they were simply a prelude to the enormous influx of Italians, Austrians, Hungarians, Russians, and Germans who would arrive between 1880 and 1930. Today, mass European immigration is much a thing of the past. Most of today’s immigrants originate from Hispanic, Asian, or Polynesian countries.

Looking at the timeline, notice how immigration patterns have reflected national and worldwide events. For instance, observe how immigration rates declined suddenly around 1860, when the Civil War began, then took off after 1880, about the time steam-powered boats had become more common, making an ocean voyage much faster and less miserable. Immigration almost came to a halt during the Great Depression of the 1930s and remained low during World War II as U.S. domestic policy remained generally opposed to mass immigration. Since WWII, the rate of immigration has risen steadily as the economy has improved and various social movements have cleared the way for greater social equality.

Every immigrant who has come to America has come from different circumstances for different reasons. Each faced unique challenges making the immigrant’s journey and finding acceptance in a new land. But each brought a unique culture and history that has contributed significantly to America’s character, culture, and personality.

The following paragraphs briefly tell the stories of several immigrant groups. Some groups’ stories will be told in greater detail in the next lesson, but no single story can represent the entire American immigrant experience. The stories included here offer only a glimpse into a significant chapter of America’s history.

In the mid 1800s, Irish farmers often worked for a living on land someone else owned. These tenant farmers, as they were called, paid their rent to their landowners in the form of cash or produce. Potatoes were the primary crop in Ireland at the time, so when a massive potato famine struck in the 1840s, many tenant farmers could not pay their rents. Weakened by hunger and despair, many fled to America in ships’ holds that only allotted twelve square feet to each adult. Passengers had to supply and cook their own food on deck as the weather permitted, so many died of typhus and other diseases.10

To this day, Germans have made up the largest immigrant group in U.S. history. Between 1870 and 1925, they were part of a well-organized immigration movement that added significantly to the United States’ labor force. Driven by war, oppression, famine, and poverty, these and other immigrants from eastern, northern, and southern Europe fled to America to join relatives or strike out on their own as pioneers. For these European immigrants, crossing the Atlantic took less than two weeks. Many traveled third-class in steerage compartments carrying as many as 1,500 passengers.11

Most Asians who came to America in the 1800s came to work. Young Chinese and Japanese men journeyed to America with the intent to earn a fortune and return to their homelands wealthy enough to support a family. Most settled in the West and worked as miners, fishermen, menial laborers, service workers, railroad builders, or farmers. Unfortunately, few actually earned enough money to return to their homelands. When the U.S. economy worsened in the 1870s, most Asians faced hostility and discrimination from European-Americans, who blamed the nation’s high unemployment on the Asians’ willingness to work for low wages.12

Since 1965, several hundred thousand Cubans have tried to cross the ninety-mile passage to Florida on small boats and homemade rafts. Beginning in 1972, tens of thousands of Haitians boarded sailboats and other local watercraft in an attempt to flee the brutal regime of Haiti and cross the 600 miles of open water to the United States. Uncounted numbers of both Haitians and Cubans have died in their hopeful journey for freedom. Many have been turned back by the U.S. Coast Guard, which has been ordered to prevent unauthorized immigration.13

For more information on immigration history, go to the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. website.

1. The Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. “The Peopling of America: Pre–1790.”

2. The Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. “The Peopling of America: Pre–1790.”

3. U.S. Census Bureau. Table 1. United States—Race and Hispanic Origin.

4. Olaudah Equiano: the Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. http://history.hanover.edu/texts/equiano/equiano_contents.html.

5. abundant, plentiful

6. negligent greed

7. The Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. “The Peopling of America: Pre–1790.”

8. The Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. “The Peopling of America: Pre–1790.”

9. From Revolution to Reconstruction and What Happened Afterwards. An Outline of American History (1994). Chapter Eight: A Nation of Nations (6/6).

10. Mystic Seaport. “Coming to America: Early European Arrivals.”

11. Mystic Seaport. “Coming to America: The Peak of European Immigration.”

12. Mystic Seaport. “Coming to America: East Asian Immigration.”

13. Mystic Seaport. “Coming to America: Cuban and Haitian Immigration.”