A free press is a truly unique phenomenon. It does not seem to exist on its own. For a society to support a free press, its members must exercise self-control. Inevitably, someone is bound to publish material that is unpopular or embarrassing—something that harms another individual’s reputation or creates social unrest, or something that places the government or another organization and its leaders in a poor light. Whenever this occurs, people tend to rise up and try to stop that material from being published. Such a reaction seems to be a part of human nature.

English rulers were no exception. In 1275 the British Parliament made it a crime to “tell or publish any false news or tales whereby discord1 or occasion of discord or slander2 may grow.” Imagine trying to write or print anything under that kind of rule. You could never be too sure that anything you wrote would be safe. Anybody could accuse you of printing offensive material capable of creating a disturbance.

During his reign, King Henry VIII created a list of banned books and required printers to be licensed before they could print anything. This gave the king great control over the information that his subjects could receive. Printers had to obtain a license and print only material that would not offend the king, or they would be charged with treason and tried before a Star Chamber court. Star Chamber court proceedings occurred in secret and were led by the king’s ministers. Many “unlicensed” printers were found guilty and beheaded or sentenced to dungeons and tortured.3

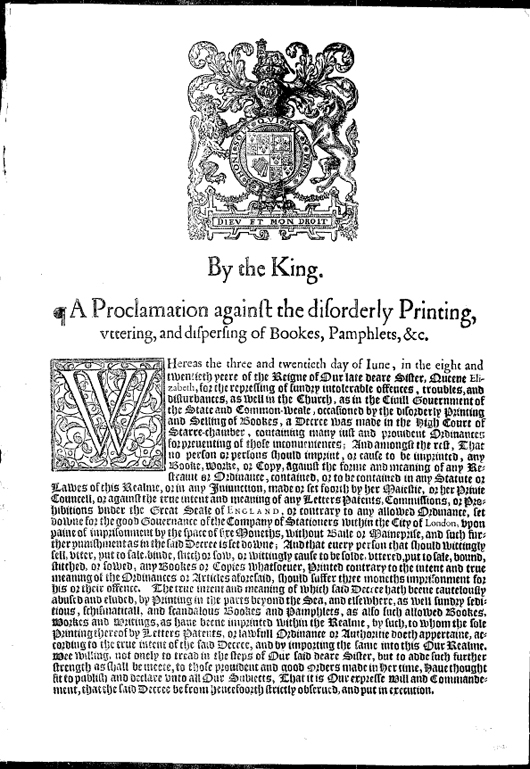

Later kings issued more decrees ordering the licensing of printers and the suppression of printed material. The following figures are examples. Imagine what would happen today if an American president or Congress issued such a decree. Americans would be up in arms almost immediately! It seems almost ridiculous to us that a ruler could go so far as to proclaim the suppression of unlicensed news and books. But that was the way things were in those times. Fortunately, times were changing.

Early American colonists were hungry for news. They would often rush to incoming ships to gather newspapers from the motherland (England). In an attempt to feed this hunger, some colonial Americans attempted to publish local newspapers. The first such attempt was a newspaper entitled Publick Occurrences Both Foreign and Domestick, edited by Benjamin Harris and published on 25 September 1690. It was both unauthorized and critical of the Crown. Massachusetts Bay officials shut the paper down after the first issue with a warning against all future unlicensed publications of any kind.

The next colonial newspaper, the Boston News-Letter, was not printed until 1704. From there, a string of newspapers began to appear in the colonies. They competed against each other and against the officially authorized papers of the day. One of the newspapers, the New York Weekly Journal (see figure at right), printed and published by John Peter Zenger, competed against the officially authorized New York Gazette.

Until that time, British common law went to great lengths to try to protect a person’s reputation. If printers were not careful, they could wind up facing accusations of libel. At the time, libel meant any written statement or accusation that damaged another person’s reputation. A publication that placed anyone’s reputation in a poor light was considered libelous.4 Printers who were found guilty of libel were punished by the law. It didn’t matter if what they had printed was true. The popular saying of the day was “the greater the truth, the greater the libel.”

An accusation of libel took John Peter Zenger and his Weekly Journal to the courts in a trial that changed the course of journalism history and won a significant victory for freedom of the press in the Americas.

The following passage comes from the book Freedom of the Press: A Continuing Struggle by M. L. Stein. It tells the story of Peter Zenger’s trial. As you read, pay special attention to the argument of Zenger’s lawyer, Andrew Hamilton. What principles did Hamilton base his argument on? Who did he say would be affected by the decision of the jury? What was the jury’s verdict? How do you think the jury’s decision affected the freedom of the press?

John Peter Zenger didn’t seem to fit the role. He was a clumsy writer and only a fair printer. In 1733, after an apprenticeship with another printer, Zenger established the New York Weekly Journal which, even by colonial standards, was an unimpressive newspaper. It was a small, four-page sheet with wobbly type and dull make-up. Zenger earned part of his income by odd-job printing.

The royal governor in New York at the time was William Cosby, a corrupt tyrant hated by the colonists. A rascal to the core, he was accused, among other things, of making money on a treaty signed with the Mohawk Indians.

Opposition formed against Cosby’s rule and Zenger’s paper was selected as a weapon to fight the governor. James Alexander was believed to be the editorial talent behind the Journal’s content.

Zenger might have slipped into obscurity, along with numerous other colonial printers, except for a callous6 blunder by Cosby. He fired Chief Justice Lewis Morris, one of the colony’s most revered7 figures, and replaced him with the young son of a personal friend. Zenger and his supporters lashed out at Cosby in a Journal article supposedly written by a man who had left New York for Philadelphia. It read in part:

“We see men’s deeds destroyed, judges arbitrarily8 displaced, new courts erected without the consent of the legislature, by which it seems to me, trials by juries are taken away when a governor pleases; men of known estates denied their votes, contrary to the received practice, the best expositor9 of any law. Who is there in that province that can call anything his own or enjoy any liberty longer than those in the administration will condescend10 to let them do it, for which reason I left it, as I believe more will.”

The enraged Cosby ordered copies of the Journal burned, but the little weekly kept up its attack. The governor destroyed more copies, terming the allusions to his rule “scurrilous,11 scandalous and virulent reflections.” He posted a reward of fifty English pounds for the identity of the author of the articles. Finally, the attorney general charged Zenger with criminal libel, thereby setting the stage for one of the most famous trials in American history.

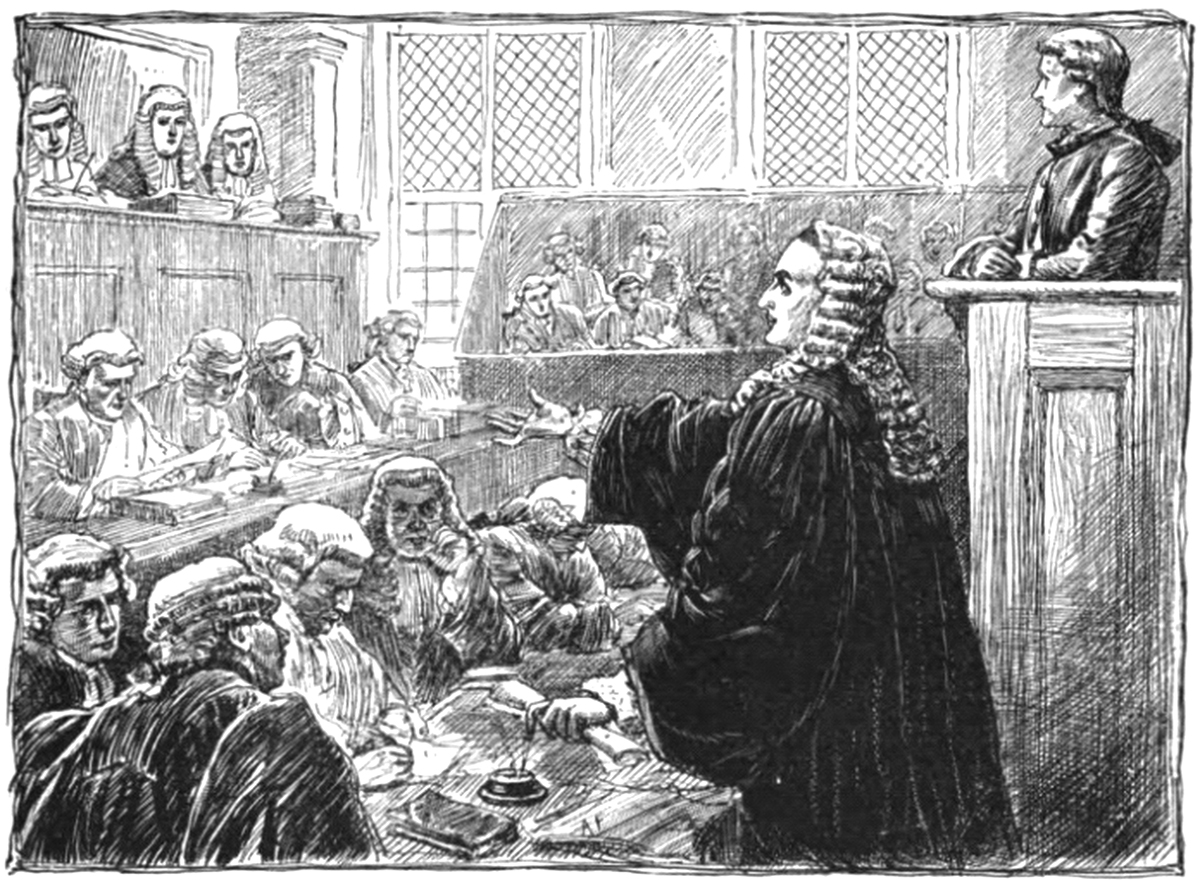

The Famous Zenger TrialArtist: Alfred Fredericks, from Wall Street in History by Martha J. Lamb, page 29.

The Famous Zenger TrialArtist: Alfred Fredericks, from Wall Street in History by Martha J. Lamb, page 29.

On a hot, sticky August day in 1735, Zenger, who had lain in prison for nine months for lack of bail, appeared in court. He was represented by an eighty-year-old lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, a friend of Benjamin Franklin. Hamilton admitted the publication of the articles and then proceeded to justify them in a stirring plea to the jury, asking it to consider the truth of the Journal’s charges.

“The question before the court and you, gentlemen of the jury, is not of small or private concern,” Hamilton pointed out. “It is not the case of a poor printer, nor of New York alone, which are trying. No! It may, in its consequences, affect every freeman that lives under a British government, on the main of America. It is the best cause; it is the cause of liberty; and I make no doubt but your upright conduct this day will not only entitle you to the love and esteem of your fellow citizens, but every man who prefers freedom to a life of slavery, will bless you and honor you as men who have baffled the attempts of tyranny; and by an impartial and uncorrupt verdict, have laid a noble foundation for securing to ourselves, our posterity, and our neighbors, that to which nature and the laws of our country have given us a right—the liberty—both of exposing and opposing arbitrary power in those parts of the world at least, by speaking and writing truth.”

The jury found Peter Zenger not guilty and there was rejoicing in the streets of New York that night. Friends hoisted12 the smiling printer on their shoulders as bonfires were touched off in his honor.

Andrew Hamilton appealed to truth and liberty. The question he laid before the jury was whether Peter Zenger should be punished for libel when all he did was publish the truth. He asked the jury to support the people’s right and liberty to expose rulers who abuse their power. The jury’s decision, he pointed out, would not be limited in its effect to just Peter Zenger. It would affect every person under British rule. It would “baffle the attempts of tyranny.”

The jury’s “not guilty” verdict was a landmark decision for freedom of the press. It gave American writers and printers more liberty to comment on the government and its activities without fear of punishment

After the Revolutionary War, the American Founders set out to create a new system of government that would protect natural rights (life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, etc.) and give the American people the power to direct the course of their government. They created a list of inalienable rights, rights that they felt nobody had the right to limit or take away. The list consisted of ten amendments to the Constitution and was called the Bill of Rights.

Freedom of speech and freedom of the press took their place right in the middle of the First Amendment.

Obviously the Founders felt strongly about these rights and their importance. Many of them wrote passionately in defense of these freedoms, particularly freedom of the press. By reading their comments, we can more closely understand why they felt this freedom was so important and why they placed it in the Constitution.

The following segment comes from a letter written by Thomas Jefferson in 1787 to Edward Carrington, a U.S. Representative from Virginia. Jefferson was a firm believer in the virtues of a free press. Although Jefferson later accused the press of being irresponsible and selling lies for money, he never changed his position that the press should go unregulated.

Jefferson wrote this letter in the wake of Shay’s rebellion, an uprising of farmers in Massachusetts led by Daniel Shay. At the time of the letter, the United States was still governed by the Articles of Confederation, a predecessor to the Constitution. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights had yet to be drafted, although the Constitutional Convention was only months away from convening.

As you read the passage, consider the following questions: According to Jefferson, what is the basis of our government? Who is responsible for making sure the government is doing its job correctly? Can the American people be trusted to make good decisions? What do American citizens need to make informed decisions? What would happen if the American people were not informed about government happenings?

The tumults14 in America I expected would have produced in Europe an unfavorable opinion of our political state. But it has not. On the contrary, the small effect of those tumults seems to have given more confidence in the firmness of our governments. The interposition15 of the people themselves on the side of government has had a great effect on the opinion here. I am persuaded myself that the good sense of the people will always be found to be the best army. They may be led astray for a moment, but will soon correct themselves. The people are the only censors16 of their governors: and even their errors will tend to keep these to the true principles of their institution. To punish these errors too severely would be to suppress the only safe-guard of the public liberty. The way to prevent these irregular interpositions of the people is to give them full information of their affairs thro’17 the channel of the public papers, and to contrive18 that those papers should penetrate the whole mass of the people. The basis of our government being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.19 But I should mean that every man should receive those papers and be capable of reading them. I am convinced that those societies (as the Indians) which live without government enjoy in their general mass20 an infinitely greater degree of happiness than those who live under European governments. Among the former, public opinion is in the place of law, and restrains morals as powerfully as laws ever did any where. Among the latter, under pretence21 of governing they have divided their nations into two classes, wolves and sheep. I do not exaggerate. This is a true picture of Europe. Cherish therefore the spirit of our people, and keep alive their attention. Do not be too severe upon their errors, but reclaim them by enlightening them. If once they become inattentive to the public affairs, you and I, and Congress, and Assemblies, judges and governors shall all become wolves. It seems to be the law of our general nature, in spite of individual exceptions; and experience declares that man is the only animal which devours his own kind, for I can apply no milder term to the governments of Europe, and to the general prey of the rich on the poor.

Jefferson had a lot of faith in the good sense of the American people. In his opinion, as long as they had good information, they would eventually make good decisions and lead the government to operate in the way it should. If the people ever stopped paying attention to the activities of their elected leaders, he feared their leaders would eventually become corrupt. Jefferson obviously had strong feelings about the corrupting nature of power.

Did you notice the importance he placed on newspapers? He felt that newspapers gave people the information they needed to make good decisions. He felt that newspapers should be independent from the government and free from its control. “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government,” he said, “I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

Jefferson’s comments reflect the general feelings held by many of the American Founders. Many of the original drafters of the Constitution would eventually hold positions of power in the United States. Jefferson was no exception. He would eventually become president. While in office, he would be subjected to numerous personal attacks, many of them untrue, from newspaper articles and editorials. Although he would criticize many of the practices of the journalists in his day, he would never withdraw from his original opinion that the press should be free from government control.

James Madison, the man who drafted the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment, originally proposed two amendments regarding free speech and a free press. Examining his proposals gives us a chance to see what he and the other Founders may have been thinking when they wrote the First Amendment.

The proposed amendments were as follows:

The people shall not be deprived or abridged22 of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments;23 and the freedom of the press, one of the great bulwarks24 of liberty, shall be inviolable.25

No state shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or of the press.

As you can see, the First Amendment as we know it was essentially taken from the first of Madison’s original two proposals. Congress did not support the second proposal, which prohibited the states as well as Congress from violating freedom of speech and of the press.

Madison actually felt that his second proposal was “the most valuable amendment on the whole list.” Not until the 1920s did the Supreme Court rule that, because of the Fourteenth Amendment, the First Amendment applied to state governments as well.26

Madison firmly believed in the importance of a free press. His sentiments echo Jefferson’s. In his own words:

A popular27 Government without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue28 to a Farce29 or a Tragedy30 or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance, and a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power knowledge gives.31

In other words, a government by the people, for the people, and of the people, is a joke if the people don’t know what’s going on. People need information because knowledge is power. Hence the need for a free press.

These were cutting edge philosophies. It’s remarkable that the Founders went to such lengths to secure these freedoms for the people they would one day govern. By doing so, they limited their own powers as national leaders.

It took a revolution, not just a war, but a revolution of thought, a revolution of ideas, of laws, and of government, to bring us the rights that we enjoy so readily today. It took a rare group of leaders who were not seeking for power but who were seeking for the good of their fellow citizens and the good of the world. They exercised commitment to principles and self-discipline that have been unmatched through much of history.

So next time you watch the news or post a message in a chatroom, remember that your right to do so exists because of the commitment and sacrifice of people who lived generations ago. The heritage they left rests at the heart of America’s character.

1. lack of agreement or harmony; conflict, quarreling

2. speaking false charges that damage or misrepresent another person’s reputation

3. Stein, M. L. Freedom of the Press: A Continuing Struggle. New York: Julian Messner, 1972, pp. 13–14.

4. containing libel

5. Stein, M. L. Freedom of the Press: A Continuing Struggle. New York: Julian Messner, 1972, pp. 13–14

6. heartless; without emotion

7. respected; esteemed

8. unrestrained; not governed by law; up to the personal preferences of the ruler or judge

9. commentator

10. agree; consent; comply

11. vulgar; evil; containing obscenitites, abuse, or slander

12. lifted

13. Kurtland, Philip, and Ralph Lerner, eds. “Jefferson to Carrington, January 16, 1787.” The Founder’s Constitution, vol. 5, Amendment I (Speech and Press), doc. 8. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1987.

14. commotions, riots, uprisings, etc.

15. involvement, interference, placement in the middle of something like a controversy

16. government officials who read printed material and delete anything considered sensitive or harmful

17. through

18. plan, devise

19. the second of two

20. population; society

21. false show

22. limited, cut short

23. ideas, notions, attitudes, thoughts, judgments

24. a solid wall-like structure raised for defense; a strong support or protection

25. unable to be violated

26. Linder, Dave. “Introduction to the Study of Constitutional Law.” Exploring Constitutional Conflicts.

27. involving everybody; governed by the people

28. introduction to a play or literary work

29. a highly improbable play; a comedy

30. a drama with a disastrous ending; often the fall of a great person or, in this case, society

31. James Madison Project. “About the James Madison Project.” http://www.jamesmadisonproject.org/index.php?page=homepage.