Before we can understand how free enterprise affects us as Americans, we need to get a working definition of the term. The American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.) defines free enterprise as “the freedom of private businesses to operate competitively for profit with minimal government regulation.”

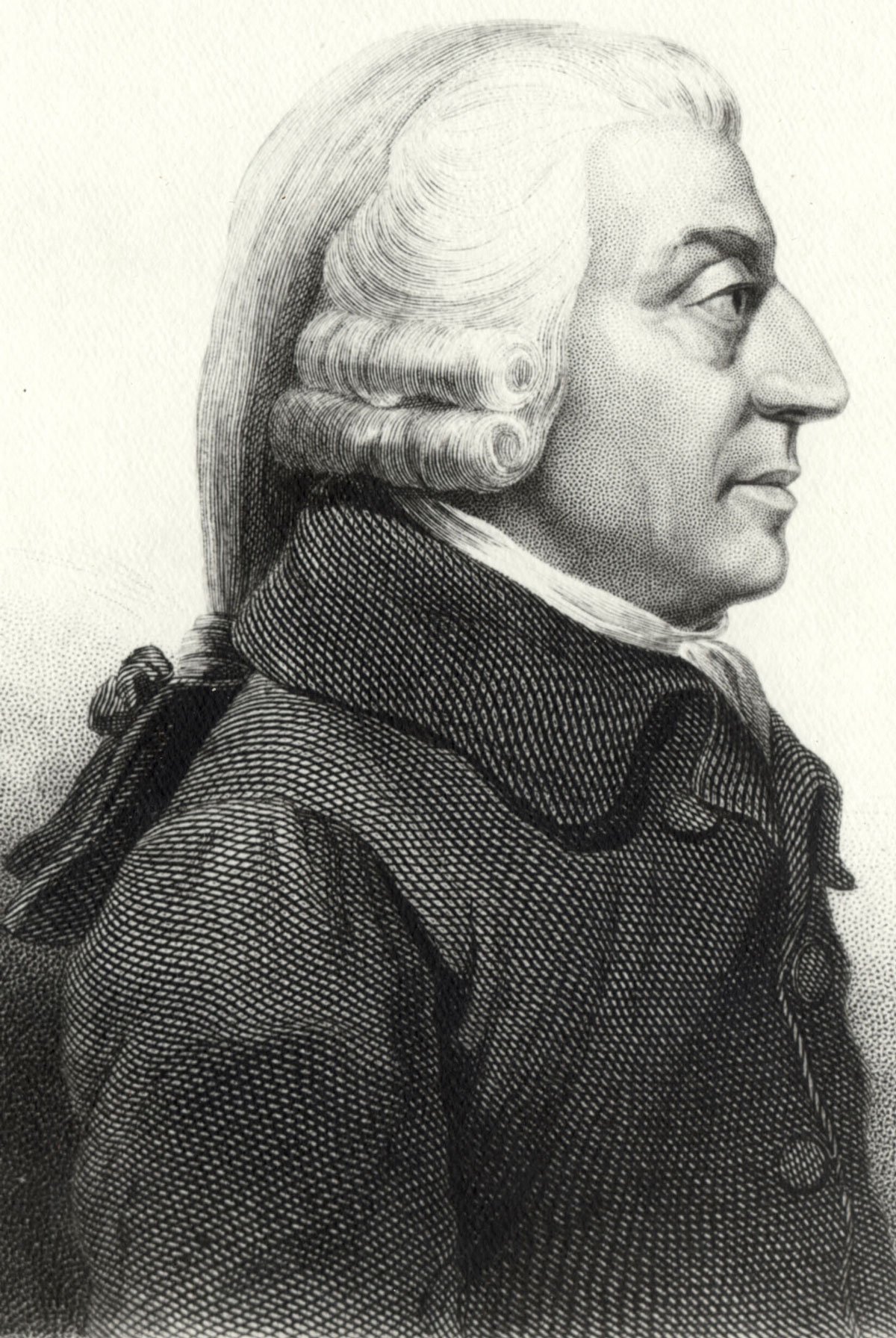

So where did we get free enterprise, anyway? The fact is, it took thousands of years and some of the greatest thinkers in history to create the system of free enterprise that we enjoy today. The year 1776 is the most important date in the development of economic freedom. On July 4, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, which asserted the inalienable rights of mankind to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. This document paved the way for freedom in the American colonies. Of equal importance—to American free enterprise, at least—was the publication later that year of a book entitled The Wealth of Nations by a Scottish economist named Adam Smith.

Considered to be “the father of economics,” Smith believed that if each person in a society were allowed to pursue his or her own self-interest, the society would become wealthy and prosperous. The following paragraph from The Wealth of Nations illustrates this philosophy, which has become the foundation of American free enterprise.

As every individual, therefore, endeavors as much as he can to employ his capital1 in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its products may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labors to render the annual revenue of society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest or knows how much he is promoting it. . . . he intends only his own gain, and he is in this . . . led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for that society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.2

What Adam Smith is trying to say here is that if each person is free to do his or her own thing for a living, society will be better off. When allowed to pursue their own self-interests, individual people are guided by an “invisible hand” to promote the interests of the whole society.

Smith’s ideas heavily influenced the early economic development of the United States of America, which guaranteed to everybody who could get here the freedom not only to choose their vocation in life, but also to keep the earnings. The Founding Fathers, many of whom signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, understood the importance of free enterprise in the development of the United States.

The free enterprise, or free market, system is based on a number of complicated factors. Let’s simplify things as best we can by discussing four key aspects of free enterprise in America: the concept of laissez-faire; exchange, specialization, competition, and profit; supply and demand; and incentive.

Laissez-faire is a French phrase that simply means “let alone.” Although you have probably never used this word before in your life, you are certainly familiar with the idea. Have you ever wanted to do something that you felt was in your best interest, but someone interfered? You may have felt like saying, “Hey, leave me alone!” Well, that’s essentially what each individual can say to the government in a laissez-faire economy when it comes to matters of business. Now, of course, businesses still have to pay taxes and obey the laws. But, for the most part, the government leaves them alone and lets them run their own businesses. That’s what laissez-faire means—government intervention is minimal.

In his first inaugural address as President of the United States, way back in 1803, Thomas Jefferson summed up the principle of laissez-faire in these words:

A wise and frugal3 government. . . shall leave [people] otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labour the bread it has earned. This is the sum of good government.

Just because the government can’t tell you what to sell and how much to sell it for doesn’t mean there aren’t any rules for selling something. In fact, the free market itself sets the rules. I’m sure you’d agree that you can only sell something if someone else is willing to buy it. So, in order to make an exchange, both parties must agree on the terms, and both must see themselves as better off.

Another wonderful thing about a free enterprise, or free market, system is something called specialization. Specialization means that each person in a free society chooses one or two specific things to do for a living. It is a great blessing! Try to imagine a world where nobody specialized. You would have to make your own clothes, your own car, your own TV, and grow all your own food. The primary reason we don’t have to do all of that is because people specialize in doing one thing very well. Each person is able to enjoy a wide variety of goods and services. This wouldn’t be possible if no one specialized.

A good example of specialization is the assembly line used to create the Ford Model T automobile in the early part of the twentieth century. Each person on the assembly line had a specific job. One man put the steering wheel on. That’s all he did all day—just put the steering wheel on each car that passed. Since that was all he did for days on end, he got pretty efficient at it. Another man installed the front wheels—he did nothing else. He, too, became extremely good at putting wheels on fast. Each person did his specialized job so well that the Ford Motor Company could produce a new Model T—a complete car—every ten seconds. Because everybody on the assembly line specialized in a single task, they were able to work together to produce a car much faster than any one person on the line could produce by himself. This is how specialization works in a free market economy—everyone does his or her own specific thing, and becomes really good at it. As a result, everyone can enjoy a wide variety of quality products

In spite of all its benefits, a free enterprise system could not work if there were no competition between businesses. Competition is good for you as a consumer because you can shop around and get the best deal for something. Competition keeps prices as low as possible. The reason we have competition in a free enterprise system is because the competing businesses want to make as much profit as possible by selling more products than their competitors. Profit is vital to a free enterprise system. As one economist describes it:

Profit is the lifeblood of a free economy. The opportunity to make a profit—or the corollary,4 the spur5 of every possible loss—is the “invisible hand” that provides our essentials and our comfort, completely automatically, and in an economic system so vast and complex that no person can even describe it. . . In guiding the economy to the satisfaction of society’s requirements, the profit system does what no central authority is capable of doing—even granting that the authority6 might be staffed by the most able managers among us. It is one thing to take a relatively primitive economy and direct its efforts toward a few types of output—say steel, or submarines, or rocketry. It is quite another thing to direct a more developed and vastly more complex economy, the purpose of which is to satisfy the whole infinite range of human goals and wants.7

You can think of profit as the amount of money someone makes when they sell something, once all the costs of producing or obtaining it have been subtracted. For example, say you bought a package of twelve Milky Way candy bars for $6 (so you paid fifty cents for each candy bar). The $6 represent your initial investment—your costs. Costs include things like operation costs and wages for employees. Then you turn around and sell the candy bars individually for a dollar each. Assuming you sold them all, you now have $12 in your hand. Your profit is the difference between what you paid for the candy bars and what you have now—it would be $6.

In a free enterprise system, the more profit a business generates, the better. So why don’t businesses just mark up their prices? Wouldn’t that give them more profit? It would if people were willing to pay that much. But people usually aren’t willing to pay more for something than they think it is worth. According to the law of demand, as the price of a good or service rises, people will buy less of that good—assuming that other factors that influence demand (like fads and personal income) don’t change. People look for less expensive alternatives when prices rise. But when demand for a product increases regardless of its price, the price of the product rises. That is the law of demand.

The law of supply is complementary to the law of demand. It says that as the price of a particular good or service goes up, businesses will produce more of that good or service. And the more popular a particular product is, the more people are willing to pay for it.

Look at prices as if you were operating a business—when people are paying more for something, you are going to make more of it. This will allow you to make a bigger profit. So supply and demand work together to determine the prices we pay for things.

One of the greatest things about a free enterprise system is that it provides everyone with the incentive to do their best work, and that means that we, as consumers, get quality products. An incentive is a desirable reward for doing something well. In a free enterprise system, there are positive and negative incentives. Positive incentives would be maximum profits for a company and health benefits and retirement plans for employees. These ensure that a company and employee do their best work. Negative incentives include the fear of bankruptcy and the chance of being fired. These also encourage companies and employees to do their best. Without incentives, people just aren’t willing to do most things, let alone do them well.

Adam Smith noticed the importance of incentive as a teenage college student. He began his higher education at Glasgow University in Scotland. He finished his college career at Oxford University in England. Adam Smith loved Glasgow and hated Oxford. At Glasgow, the teachers were paid according to their skill. The better they did, the more they got paid, so their lectures were very exciting. At Oxford, the teachers were paid a flat salary; no matter how well they taught, they wouldn’t be paid anything more—their lectures were extremely boring. The American free enterprise system is most like Glasgow: people and businesses are motivated to produce the best products, because the best products make the most money.

One of the best ways to learn about free enterprise is to start your own business. The fact is, you can start your own business whenever you want, whether it be a lemonade stand when you’re five or a restaurant when you’re twenty-five.

The American dream has become as much a part of America’s character as baseball, fireworks, and apple pie. The beauty of American free enterprise is not that it guarantees everybody wealth and success, but that it gives people an opportunity to determine the course of their own lives. Free enterprise allows people to strive for as much success as they want to achieve, and to do so with little interference from the government.

Because of free enterprise, Americans enjoy a high standard of living. When individuals and businesses are left to pursue their own self-interests, they tend to work harder and produce more quality products. Free enterprise allows everybody to specialize in that which they do best and to benefit from exchange. In short, free enterprise opens the door a little more widely for Americans to access the rights promised in the Declaration of Independence: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

1 . accumulated goods devoted to the production of other goods; often money

2. Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, part 2, New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1902, 160-161, Google Books.

3. careful; moderate

4. something that naturally flows

5. stimulus to action

6. government or controlling organization

7. SMS, 24–25