To help you really understand the Declaration of Independence, let’s first talk about what life was like at the time it was written, when the United States was still part of England. As you read, imagine you are there experiencing it for yourself.

When the Continental Congress appointed George Washington to be the general of the colonial army in 1775, volunteers were fighting a scattered war against a British army that was much better equipped. The British had the finest navy in the world, well-trained soldiers, and sufficient supplies to wage a war. The colonies had only a few merchant ships, undisciplined volunteer soldiers, very few supplies, and little ammunition. When Washington arrived in Boston to take charge of the army, he found officers who didn’t know how to give orders and soldiers who didn’t know how to take orders. Many of the soldiers had committed to serve for only a short period of time, and that time was nearly up. One British officer thought that “an experienced sheep herder” could have won the war against the colonies.

The Continental Congress had written the Olive Branch Petition to the British King, George III, hoping that peace could be restored. King George refused to read it when it arrived in England. The day after sending the Olive Branch Petition, the Congress issued a proclamation that declared the right to defend themselves against attack.

Not everyone in the Congress believed it would be necessary to declare independence from England. Many people believed the war would soon be over and they would still be a part of the British Empire, with the added benefit of increased rights. Then Thomas Paine wrote a pamphlet called Common Sense, which convinced many colonists that independence was necessary. Paine helped the colonists see that they could gain advantages in the war and, more importantly, become a free country.

With this information in mind, let’s look at the Declaration of Independence. It was written by Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. The following is only a portion of the document.

The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel1 them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident,2 that all men are created equal, that they are endowed3 by their Creator with certain unalienable4 Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving5 their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive to these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish6 it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence,7 indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient8 causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn,9 that mankind are more disposed10 to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations,11 pursuing invariably the same Object evinces12 a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism,13 it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.—Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid14 world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. . . .

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress15 in the most humble terms: our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable16 jurisdiction17 over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity18. . . . We must, therefore, acquiesce19 in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

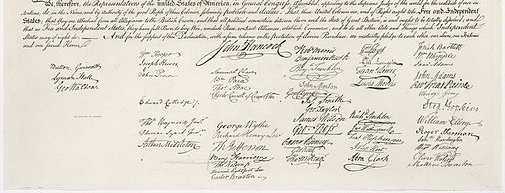

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude20 of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which independent states may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Have you ever wondered what happened to the signers of the Declaration? In making such a bold statement to a powerful country, they were putting their lives on the line. The last line of the document shows just how certain they were that the declaration would lead to trouble:

And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Although they relied on divine providence for protection, they also realized that they could be required to make great sacrifices, perhaps even of their lives and their wealth in defense of the truths they supported. The following reading passage lists some of the many sacrifices made by these great men.

What Happened to the Signers of the Declaration of Independence?21

Five signers were captured by the British and brutally tortured as traitors. Nine fought in the War for Independence and died from wounds or from hardships they suffered. Two lost their sons in the Continental Army. Another two had sons captured. At least a dozen of the fifty-six had their homes pillaged22 and burned.

What kind of men were they? Twenty-five were lawyers or jurists. Eleven were merchants. Nine were farmers or large plantation owners. One was a teacher, one a musician, and one a printer. These were men of means and education, yet they signed the Declaration of Independence, knowing full well that the penalty could be death if they were captured. . . .

In the face of the advancing British Army, the Continental Congress fled from Philadelphia to Baltimore on December 12, 1776. It was an especially anxious time for John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress, as his wife had just given birth to a baby girl. Due to the complications stemming from the trip to Baltimore, the child lived only a few months.

William Ellery’s signing at the risk of his fortune proved only too realistic. In December 1776, during three days of British occupation of Newport, Rhode Island, Ellery’s house was burned, and all of his property destroyed.

Richard Stockton, a New Jersey State Supreme Court Justice, had rushed back to his estate near Princeton after signing the Declaration of Independence to find that his wife and children were living like refugees with friends. They had been betrayed by a Tory sympathizer who also revealed Stockton’s own whereabouts. British troops pulled him from his bed one night, beat him and threw him in jail where he almost starved to death. When he was finally released, he went home to find his estate had been looted, his possessions burned, and his horses stolen. Judge Stockton had been so badly treated in prison that his health was ruined and he died before the war’s end. His surviving family had to live the remainder of their lives off charity.

Carter Braxton was a wealthy planter and trader. One by one his ships were captured by the British navy. He loaned a large sum of money to the American cause; it was never paid back. He was forced to sell his plantations and mortgage his other properties to pay his debts.

Thomas McKean was so hounded by the British that he had to move his family almost constantly. He served in the Continental Congress without pay and kept his family in hiding.

Vandals or soldiers or both looted the properties of Clymer, Hall, Harrison, Hopkinson, and Livingston. Seventeen lost everything they owned.

Thomas Heyward, Jr., Edward Rutledge, and Arthur Middleton, all of South Carolina, were captured by the British during the Charleston Campaign in 1780. They were kept in dungeons at the St. Augustine Prison until exchanged a year later.

At the Battle of Yorktown, Thomas Nelson, Jr. noted that the British General Cornwallis had taken over the family home for his headquarters. Nelson urged General George Washington to open fire on his own home. This was done, and the home was destroyed. Nelson later died bankrupt.

Francis Lewis also had his home and properties destroyed. The British jailed his wife for two months, and that and other hardships from the war so affected her health that she died only two years later.

“Honest John” Hart, a New Jersey farmer, was driven from his wife’s bedside when she was near death. Their thirteen children fled for their lives. Hart’s fields and his grist mill were laid waste. For over a year he eluded capture by hiding in nearby forests. He never knew where his bed would be the next night and often slept in caves. When he finally returned home, he found that his wife had died, his children disappeared, and his farm and stock were completely destroyed. Hart himself died in 1779 without ever seeing any of his family again.

To obtain their dream of independence, the Founding Fathers worked for years and made many sacrifices. They are great examples of what it takes to achieve the American dream even in the most difficult circumstances. What kind of people do you think they were? What attributes helped them to succeed? The attribute that I see most in their stories is courage. They were courageous and determined in the face of overwhelming difficulty. We will see these traits in people throughout the unit.

Have you ever wanted to write a declaration of your own independence? What would it say? Have you ever taken a stand for something you felt was important, even though there were difficult consequences? Why did you do it?

Write your answers on a separate sheet of paper and title it “Independence Papers.” You will not be graded for this activity.

1. drive, motivate

2. obvious

3. gifted

4. not able to be taken away

5. getting

6. get rid of

7. good judgment

8. quickly passing

9. shown

10. inclined

11. something forcefully taken

12. shows

13. system of government where the ruler has unlimited power

14. unbiased

15. correction

16. unjustified

17. control; power to govern or legislate

18. generosity

19. give in

20. rightness

21. “What Happened to the Signers of the Declaration of Independence?” Quoted on Bethlehem PA Online, (accessed August 27, 2014).

22. looted and plundered