The United States Congress is the chief legislative, or lawmaking, body in the land. Through the laws it passes, it defines crimes and punishments, establishes levels of taxation and spending, and creates the programs and policies that shape American government and politics. The Constitution also formally grants to Congress the power of the purse, which means that only Congress can raise and spend taxes. Congress also reserves the right to declare war, even though the president is the commander in chief. Because it holds this power, Congress is significantly involved in the establishment and regular review of the Pentagon, State Department, and other foreign policy budgets and activities.

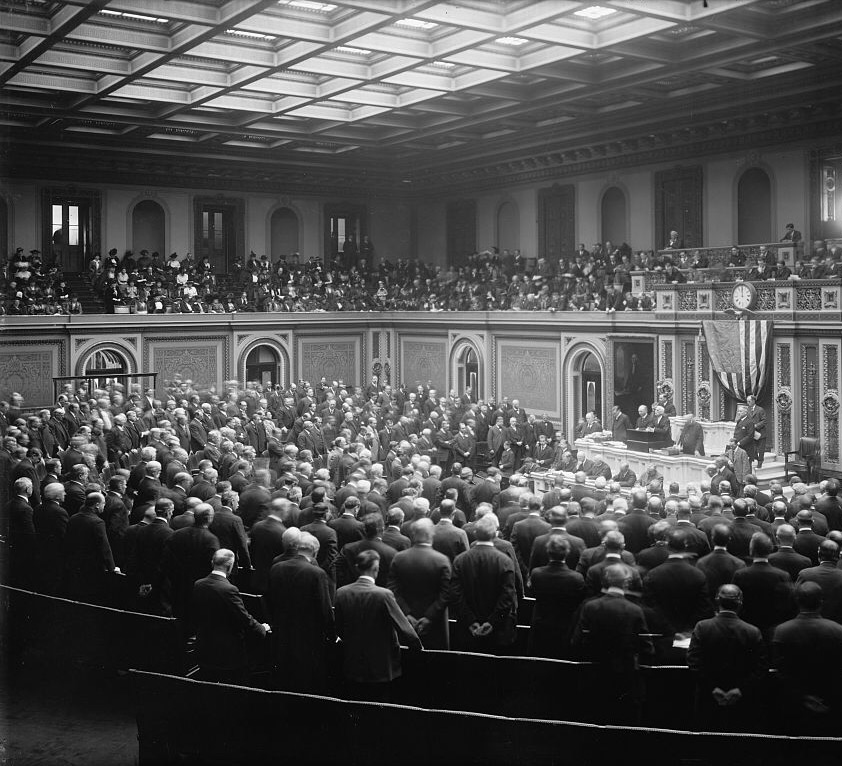

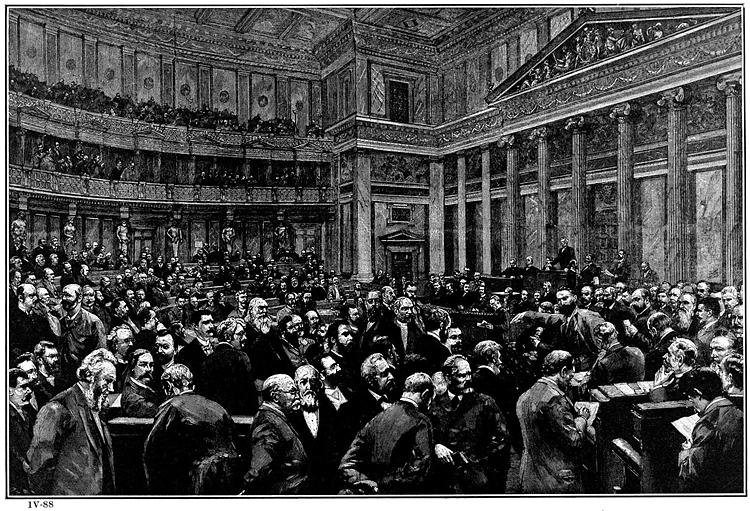

As established by the Constitution, Congress is composed of two separate legislative bodies—the House of Representatives and the Senate. There are 435 members of the House and 100 members of the Senate. In the House, each state is allocated a proportion of the 435 seats equal to the state’s proportion of the nation’s population. For example, a state with 10/435ths of the nation’s population has ten seats in the House of Representatives. In the Senate, each state is represented equally—all fifty states send two senators to represent them in Washington. Because there are 535 members of Congress, representatives and senators are more directly and frequently influenced by the people than are presidents or Supreme Court justices. The voice of the people is most directly reflected in the decisions made by Congress.

The legislative process can be long, tedious, complex, and frustrating. Indeed, it is much more difficult to pass a bill than it is to kill one. There are numerous times and places during the legislative process in which a bill can die. Only a very few survive to become law.

Although the formal legislative process begins when a bill is introduced in the House or the Senate, a bill begins long before that. By introducing a piece of legislation, a member of Congress proposes a solution to a public policy problem. Before a public policy problem can be addressed through the legislative process, however, it must first be recognized as a problem.

Once a problem is identified, possible solutions for the problem must be identified and discussed. In the American political process, there are generally more than enough proposed solutions to the problems the nation faces. The difficulty lies in sorting through the proposed solutions to find the one that will work best. When a member of Congress proposes a bill, he or she is essentially claiming to have found the best (or at least most practical) solution to the public policy problem in question.

Before a member of Congress introduces a bill in the House or Senate, the bill must be drafted. Writing legislation requires precision, attention to detail, an intimate understanding of existing laws, and a clear understanding of the proposed policy solution. Members of Congress often rely on staff, experts in the area the proposed legislation will affect, and Congressional legal staff to assist them in drafting legislation.

Members of Congress must successfully compete for congressional and public attention, or the legislation they introduce is bound to fail. Thousands of bills are introduced each year, and only a handful become law. To build support and momentum for a bill, members of Congress generally hold press conferences to announce the introduction of legislation. They will also secure as many cosponsors as possible for their legislation to provide evidence of broad congressional support for the bill.

Once a bill has been formally introduced, it is referred to a congressional committee for further consideration. There are twenty permanent committees in the House and sixteen in the Senate. Each of these committees has a specific area of legislative jurisdiction,1 and bills are generally referred to committees accordingly. In many cases, however, bills address topics that fall under the jurisdiction of more than one committee. In others, it is unclear which committee has jurisdiction over a bill. In these cases, party leaders in each house choose which committee or committees will consider the legislation.

A favorable committee assignment can mean the difference between success or failure for a bill. If a bill is assigned to a committee with a chair2 that supports the legislation, the bill is likely to be scheduled for a timely public hearing, full committee consideration, and a vote. A chair who does not support legislation can easily kill a bill by simply failing to put it anywhere near the top of the committee’s agenda. (Although members of the House or Senate, through different procedures, can bring legislation to the floor over the objections of a committee or its chair, members are very reluctant to encroach on committee jurisdiction.)

Because committees have crowded agendas and because of scheduling difficulties, many otherwise good bills die in committee simply because there is not enough time to deal with them. For this reason, committees are sometimes referred to as the “legislative graveyard.”

Most bills that are referred to a committee are also referred to a subcommittee. Once a bill has been reviewed, marked up (amended), and voted on by a subcommittee, it is returned to the full committee for further consideration. When a committee is ready to take final action on a bill, it votes to either keep the bill in the committee (thereby killing it) or send it to the floor for further consideration.

Once a bill has been considered and approved by the committee or committees to which it was assigned, it must be considered by all members of the body in which it was introduced—either the House or the Senate.

Although the majority and minority party leaders work together in the Senate to determine when bills will come to the floor and under what conditions they will be debated, the House is much more restrictive in establishing its legislative calendar. In many ways, legislative procedure in the House is much more regimented than in the Senate, partly because of the need to have more control over the larger membership in the House and partly because of tradition.

In the House, a Committee on Rules establishes the time and duration of debate on each bill that comes to the floor. In fact, each bill considered by the House comes with a rule attached to it that is created by the Rules Committee. In addition to the timing and extent of the bill’s floor consideration, the rule specifies what, if any, amendments may be made to the bill on the floor.

The Rules Committee can attach a closed, open, or modified-closed rule to each bill that comes before it. As the names suggest, a closed rule does not allow for any amendments while an open rule allows any number of amendments. Modified-closed rules, which are used most frequently, allow for only a specific number or, more often, a specific pre-approved list of amendments. In the Senate, there is no Rules Committee and hence no rules attached to Senate legislation.

In both the House and the Senate, the allotted time for debate on each piece of legislation is divided equally between the two parties. Generally, the sponsor of the bill or the chair of the committee that reported the bill will be a sort of floor manager for the legislation, allowing other members to speak in favor of the bill. A member who opposes the bill, usually from the opposing party, will manage the time for those who wish to speak against the bill.

After all allowable amendments have been offered and voted on and the time set aside for debate has expired, the full membership of the House or Senate votes on the legislation. A bill must win the support of a majority of those present to pass.

In order for a bill to move on in the legislative process, it must be passed in identical form by both the House and the Senate. If the two houses cannot reconcile their differences on a bill, it cannot be considered further, and it dies.

While we often speak of Congress as a single branch of the government, it is, in fact, made up of two distinct houses. In the House of Representatives, representation is based on state population. In the Senate, representation is equal, with each state sending two senators to Washington. There are important differences between the legislative process in the House and the Senate. Generally speaking, it is much easier for the majority party to work its will in the House than in the Senate. In the Senate, any single senator can gain control of the floor and refuse to give it up, essentially talking a bill to death. This tactic is called a filibuster. While a filibuster can be cut off by a three-fifths majority vote, the power of individual senators to delay and block legislation makes its proceedings very different than in the House.

Because both houses of Congress may amend a bill in different ways before passing it, a bill going before Congress may come out of the House and the Senate as two similar, but not identical, bills. Because similar, but not identical, bills are frequently passed by the House and the Senate, Congress has established a mechanism for resolving House-Senate differences without starting the process all over again.

When similar bills are passed by both houses, they are referred to a special, temporary “conference committee,” composed of members from both houses and both parties. Members on conference committees are charged with working out the differences between the two versions of the bill and creating a compromise version which is then sent back to each house. At this stage in the process, no amendments are allowed. The full membership of the House and Senate must simply choose to accept or reject the conference committee’s report, which details the compromise version of the bill. If the report is accepted, the bill is forwarded to the president. If not, the bill is dead.

Bills passed in identical form in both houses of Congress are sent to the president to be signed or vetoed. If the president signs the bill, it becomes law. However, if the president vetoes the bill, it is rejected, but the Congress may attempt to override the veto. A veto can be overridden if a two-thirds majority in both houses votes to do so.

The president can use the veto power as a bargaining tool in the legislative process. Because it is difficult to secure two-thirds majorities in favor of legislation in both houses, a presidential veto generally means that a bill is dead. A large majority of bills that are vetoed are not overridden. Consequently, by suggesting which provisions3 are acceptable in a piece of legislation and which ones are not, the president can influence the content of the bills Congress sends to the president’s desk. Presidents must be careful, however, not to use the veto or the threat of a veto too frequently because Congress may refuse to work with a president who attempts to bully members of Congress. This is especially true when there is divided-party government.

In 1995, Congress voted to extend the president’s veto power by authorizing the use of a line-item veto on appropriations bills. Under the conditions established by Congress, the president could use the line-item veto to lower or remove objectionable spending requests from a bill. The Supreme Court, however, ruled Congress’s attempt to alter the president’s constitutionally authorized veto power through legislation (instead of a constitutional amendment) unconstitutional. Because of this ruling, the president of the United States does not have line-item veto authority.

By creating a bicameral4 legislature with a separate executive branch with the ability to veto legislation, the Framers of the Constitution clearly intended to create a system of government in which it would be difficult to act and comparatively easy to block action. Their efforts have proven resoundingly successful. The legislative process in just the House or Senate alone is often mind-numbingly slow and complicated. Guiding a bill through two houses is a seemingly impossible task. However, each year, a sizable number of bills, a few of them significant but most of them less so, are passed by the Congress and signed into law by the president.

1. right and power to interpret and apply the law; the extent of authority or control

2. chairperson; person who leads a committee

3. parts of a bill or law that explain what rules will apply for a given situation or set of situations

4. two-part: House of Representatives and Senate